“A true warrior does not fight because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.” (G.K. Chesterton)

Twentieth century Westerns were not my only film fare growing up, readers. I saw a lot of World War II movies as well. The Longest Day, Sands of Iwo Jima, and many others played across my parents’ television screen when I was young. The films taught me to love and respect America and the Americans that make up our military better than any speech or essay could have.

I loved watching these World War II films. The sense of unity, of purpose, the will to fight and defeat evil, thrilled me. But after 9/11, I learned that the modern world was nothing like the one I saw in those movies about the “Greatest Generation.” It has taken me long years of study to learn how the “Greatest Generation” turned into the generation which protested the Vietnam War, but I am no longer confused about the gap and the change in the way that I once was.

By this circuitous route, we come to the subject of today’s post, the EWTN documentary Called and Chosen: Fr. Vincent Capodanno. Fr. Capodanno was a Catholic priest and Navy chaplain during Vietnam. He did not begin his ministry in the Navy; in fact, joining the military was the furthest thing from his mind when he entered the Maryknoll seminary in New York at the age of twenty.

Inspired as a boy by the stories of martyred missionaries who had left Maryknoll to preach to the Chinese, Fr. Capodanno entered the seminary and was ordained a priest. He was sent to Taiwan for some years, returning home to visit his family after that missionary stint. To his dismay, he learned his next assignment would not be back in his beloved Taiwan but in Hong Kong, which was not then part of Red China.

Desperate to return to Taiwan, Fr. Capodanno wrote letters to his superiors asking to be transferred there or to be sent home for another assignment somewhere else. He continued to do this even after his requests were rejected. So it was with some surprise that his superiors received an abrupt, new request from the priest: he suddenly wanted to become a Navy chaplain, and he wanted to be assigned to the Marines serving in the jungles of Vietnam.

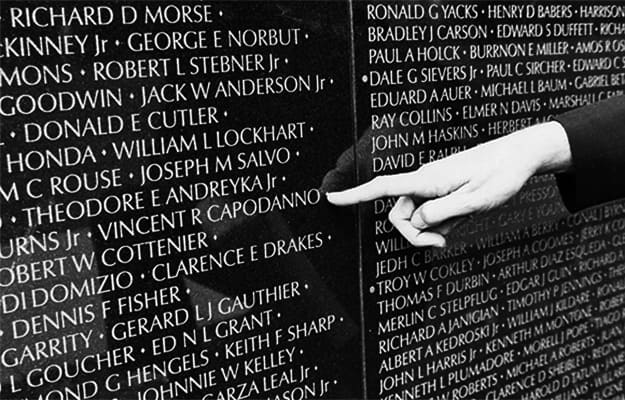

Well, any request to go to Vietnam would be surprising back in the ‘60s, when the War was being manhandled by politicians and protested vigorously by the academics, the media, and their unfortunate cohorts of young believers across U.S. campuses. Nevertheless, Fr. Capodanno’s new request was granted and he underwent a year of chaplain’s training before being assigned to the Marines. He died in combat September 4, 1967, giving the Last Rites to the Marines who died when his division was ambushed by the Viet Cong.

I will not spoil any more of the documentary for you, readers. You can find it on DVD through EWTN, Amazon, or Ignatius Press. Toward the end of the film, I had to sniff a lot to keep from crying. Fr. Capodanno’s story of love and sacrifice is moving on its own, but that is only part of the reason why this blogger had to hold back tears.

You see, even when I did not understand the stories about Vietnam completely, I did realize that the men who had served in that war were different than the “Greatest Generation.” Slowly, by degrees, I began to comprehend how they were abused by the public after they came home.

What really stymied me, however, was why they were treated like this. Referring back to the top of this article, you will recall my mention of movies about World War II. Several of these were made before the War had even ended, yet our soldiers who were fighting overseas were being cheered to the echo nonetheless. We didn’t know for a while there whether or not we would win, but the movies of that era never wavered in their morale-boosting narrative that victory was within our grasp.

The incongruence between the lionization of the “Greatest Generation” and the attacks on the Vietnam generation made so little sense to me that I did not pay very much attention to it for quite some time. Learning more about Vietnam over the years, though, I cannot convey in words the profundity of my ire for the academic/journalistic complex who mistreated our men when they came home, nor for the politicians who seized on their narrative in order to remain in power.

Now, of course, some of you will start yelling about the politics and the reasons why the Vietnam War was wrong. The politicians and people in charge of fighting the Viet Cong did not run the war effort well, I grant you; I believe a number of them actually wanted us to lose it. Their “mistakes” also gave the academics and journalists ample opportunity to attack and demoralize our military, making matters even worse. But none of this means the War itself was wrong.

More to the point, to borrow Fr. Capodanno’s answer to those who challenged him about the War’s politics, the affairs of state were no excuse to abuse our returning veterans. Our men were fighting, bleeding, and dying in Vietnam’s jungles. They were far from home, in a place they didn’t want to be, fighting for a cause no one clearly explained (the defeat of the Communists in Vietnam to preserve freedom there and in the rest of the world).

Yet the populace who should have respected them for their sacrifice was encouraged – nay, goaded – into treating them like trash when they came back. Our men returning from the Hell that was Vietnam were subsequently hounded and derided as cowards, monsters, and demons when they came home.

They were told they were more hideous than the enemy that tortured, maimed, and killed their brothers. They were told that they were worse than the Communists who used women and children as human shields, that they were as evil and cruel as the beasts who used children as suicide bombers, spies, and soldiers. They were treated as ticking time bombs that might go postal on innocent bystanders at any moment because they had been to Vietnam, where you could not tell who was friend and who was foe. They returned from hell to face a new hell; a hell where their families, friends, neighbors, and total strangers tortured them with words, actions, or petulant, suspicious silence.

Never again. I never want to see this happen to our armed forces again. For the rest of my life I will read these stories, hear these tales, and watch these documentaries with tears in my eyes. Those tears will not just be for the suffering of our men and the South Vietnamese during the war. No, they will be for the treatment our men received when they came home, and for the retribution wrought by the Viet Cong on the South Vietnamese after we left them to the Communists.

Vietnam was not a lost war. It was a war that was thrown away, the one war where we snatched defeat from the jaws of victory – we, who had saved the world in World War II, threw away a war we had won! “When I went under, the world was at war,” Cap said in The Avengers. “I wake up, they say we won. They didn’t say what we lost.”

We lost a lot. We lost a whole hell of a lot, readers. And we lost it because we threw it away.

The sense of shame I feel for what we did to our military and the South Vietnamese becomes so intense at times that it almost makes me physically sick. They did not deserve this abuse – not a one of them earned it. We went from a nation of heroes – a nation with “the Greatest Generation” – to a nation of indecisive cowards in the space of twenty years.

Never again, readers. We cannot – we must not – let this happen ever again.

When you watch the documentary, you will see that Fr. Capodanno understood what I am telling you right now. The Grunt Padre, as his Marines affectionately dubbed him, died making sure his men were safe. In a time when the American people largely regarded them as no less evil than the Communists they fought, one Navy chaplain made a difference by treating the Marines under his care as the human beings they were. You cannot listen to a description of his life in Vietnam and not consider him a hero, readers. Hero is too small a word to encapsulate what Fr. Capodanno did for these men – far too small.

I hope you get the chance to watch this documentary. At some point, I also hope to read and review the book about Fr. Capodanno, called The Grunt Padre, so I can learn more about this chaplain I admire so much. Knowing how much Fr. Capodanno did for those Marines lifts some of the guilt from my shoulders. It is good to know that not everyone in the U.S. hated the military during Vietnam; that there were those who treated our men with the honor, respect, and the love they deserved even when doing so was not popular.

It also firms my determination never to fall into the trap so many others landed in during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Attack the U.S. military at your own peril here at Thoughts on the Edge of Forever, readers. You will find that I do not accept such assaults. Period.

In closing I leave you with this video of the U.S. Marine Corps’ Hymn –

And with the prayer that God will bless you, the United States military, and the United States of America for many more years to come.